Who’s Turned On By Pregnant Women?

Early one evening late in my second trimester of pregnancy, I was standing in the dairy aisle of the grocery store, with one hand on my back and the other over the kicking baby in my distended belly. A young man approached me, initiated a conversation about the World Cup, and, casually, asked me if I’d like watch the game with him that weekend. “You’re pretty!” he whispered. I was shocked.

I wasn’t putting out a sexy vibe. (Not at all.) I had assumed that any male attention I receive in late pregnancy, including that from my husband, would be friendly, not sexual. Why would a man who is not the expectant father think pregnancy is sexy? But then other women told me similar stories about how they got hit on in third trimester. So I decided to look into it, and it turns out that a study on sexual attraction to pregnancy has recently come out.

A team of Swedish and Italian doctors, led by Emmanuele Jannini and Magnus Enquist, recruited nearly 2,200 men who had joined online fetish groups such as alt.sex.fetish and alt.sex.fetish.breastmilk. They presented a questionnaire that asked the respondents questions about their preferences for pregnant and lactating women. The survey also asked for the sex and age of each sibling, and whether the sibling is a full sibling or not (half-sibling or adopted child). Most respondents reported both a pregnancy and a lactation preference. The average age at which respondents became aware of their preference was about 18 years.

What Jannini and Enquist and their colleagues were searching for was evidence that there was something special about the upbringing of men that are secually aroused by pregnancy. They knew that a specific stimulus early in life can elicit sexual behavior when theat animal reaches sexual maturity. For instance, goats that are raised by sheep are sexually aaroused by sheep only. This is called sexual imprinting.

Is it possible that boys that are raised by women who are pregnant for much of their childhoods are unusually attracted to pregnant women?

It turns out, what’s good for the goat is good for the guy. The more exposed a man was to his mother being pregnant and breastfeeding when he was between 1.5 and 5 years old, the more likely he is, as an adult, to be sexually attracted to pregnant and breastfeeding women.

A younger sibling is the key to early exposure. The respondents who eroticized pregnancy and breastfeeding had significantly more younger siblings than expected by chance. Respondents with one sibling were older than their sister or brother in 66 percent of cases. Interstingly, siblings born of a different mother does not appear to be related to respondents’ sexual preferences. Only a boy’s own pregnant mother seemed to leave a sexual imprint.

Freud’s “oedipal phase,” from about 3 to about 5-6 years of age, only overlaps partially with the sensitive period suggested by this study’s data, the researchers are careful to point out. Sexual imprinting is different in that it’s motivated not by sexual drive but because the individual learns what’s normal during a sensitive phase of development and later seeks sexual partners that resemble his (or her) own parents.

What does this mean for women who are pregnant or plan to be pregnant? It means you may be able to predict how attracted your partner will be to you in late pregnancy. Does he have sibling born within five years after him? If so, he’s likelier to be turned on by your pregnant self.

As for the guy I met in the dairy aisle, I’d wager he had a younger brother or sister. I’d bet more on getting this right than the winner of the next World Cup.

*If you like this blog, click here for previous posts and here to read a description of my most recent book, Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, on the science behind love, sex, and attraction. If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, available October 11, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

A Kirkus Star!

Absolutely delighted that Kirkus gave “Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?” a starred review. Thank you, Kirkus!

Absolutely delighted that Kirkus gave “Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?” a starred review. Thank you, Kirkus!

—-

Popular-science writer Pincott (Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, 2008, etc.) provides a lively, accessible romp through the science of pregnancy.

Known for her previous research on love and sexual attraction, the author makes a natural transition in her latest. Delving into the science of pregnancy, parenthood and fetal development, she presents her findings with wit, personal anecdotes and playful humor. Eschewing predictable “avoid the shellfish” advice, Pincott provides a science-based trivia collection, drawing from studies in evolutionary psychology, biology, neuroscience, social science, epigenetics and more. She explores topics such as how a woman’s activities might influence her unborn baby’s personality, how pregnancy and motherhood can change the behavior of mothers and fathers, what factors might influence a baby’s gender and why the first hour after a baby’s birth means so much for mother-newborn bonding. Inspired by questions from her own first pregnancy, the author also digs up the answers to common inquiries such as “what does baby’s birth season predict?”; “what can Mozart really do?”; and “will what we eat now influence baby’s tastes later?” Despite the bombardment of information, Pincott presents her research as fun things to contemplate rather than additional things to worry about, so nervous expectant parents can thoroughly enjoy the book.

A fascinating supplement to the typical maternity guide.

IQ and Fish, the Whole Fish, and Nothing But the Fish

For the nine-plus months of pregnancy, I dutifully downed fish oil pills. I had heard all about the virtues of essential fatty acids (especially DHA, docosahexaenoic acid), known collectively as omega-3s, which are found in fish such as salmon and sardines. These fats are involved in the development of new neurons and help form the cell walls — the structural support — of nerve cells. If the healthy brain is like a sponge, then the brain deprived of omega-3 is like a puddle.

Several years ago, in 2007, an enormous study funded by the National Institute of Health looked at the link between children’s scores on aptitude tests (at ages 6 months to 8 years) and their mother’s prenatal consumption of fish. It turned out that the kids whose moms ate fish more than twice weekly during pregnancy were significantly less likely to have low scores on cognitive tests. Low maternal seafood intake (two or fewer servings weekly) was also associated with increased risk of suboptimum outcomes for prosocial behavior, fine motor, communication, and social development scores. This was a huge deal. The nearly 12,000 expectant women who participated in the study were asked to record how much whole fish they ate, not fish oil supplements.

Naturally, this study — and smaller studies like it involving whole-fish consumption — inspired millions of pregnant women to focus on fish oil.

Problem is, not many of us want to or can afford to eat fish every day. Fears of mercury and PCB contamination are valid (many varieties of fish, such as tuna, have high levels that are toxic to fetuses). It’s not much of a stretch to say that fish oil pills are a better way to get your daily DHA.

But here’s the interesting part. Everyone has assumed that when it comes to omega-3 fatty acids like DHA, the source — whole fish or fish oil pills –shouldn’t matter. Seems reasonable, but is it?

A few very recent fish oil studies cast doubt:

Results of fish oil pill supplementation range from neutral to negative…

• A review of six clinical trials (1280 women in total) involving fish oil pill supplementation during breastfeeding found no significant difference in children’s neurodevelopment: language development (intelligence or problem-solving ability, psychomotor development, motor development. In child attention there was a significant difference. For child visual acuity there was no significant difference. For language development at 12 to 24 months and at five years in child attention, weak evidence was found (one study) favouring the supplementation.

• At the Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Adelaide, Australia, researchers tracked the children of 2400 women who took DHA-rich fish oil pills in the last trimester of pregnancy. The use of these fish oil capsules compared with vegetable oil cap- sules during pregnancy did not result in improved cognitive and language development in their offspring during early childhood.

Other fish oil pill studies found disturbingly negative results:

• At the Universities of Copenhagen and Chapel Hill, researchers followed 120 Danish women who nursed their babies for four months after birth and took fish oil supplements (or olive oil pills). The children were tested in intervals up to seven years. The higher the early intake, the lower the child scored in speed of information processing, inhibitory control, and working memory tests. Boys whose mothers consumed fish oil had lower prosocial scores relative to the olive oil group.

Meanwhile, these recent studies strengthened the evidence that eating fish is brain-boosting:

• In a study that took place the Arctic, 154 11-year-old Inuit children took standardized tests for memory and verbal learning. Their scores were compared with their levels of DHA present in their cord blood at birth. Children who had higher cord plasma concentrations of DHA at birth achieved significantly higher scores on tests related to recognition memory processing. The source of DH in their mothers’ diets was fish and marine mammals. Intriguingly, the connection with higher test scores remained intact regardless of seafood-contaminant (PCB and mercury) amounts.

* A UK study of 217 nine-year-olds whose mothers had eaten oily fish in early pregnancy had a reduced risk of hyperactivity and children whose mothers had eaten fish (whether oily or non-oily) in late pregnancy had a verbal IQ that was 7.55 points higher than those whose mothers did not eat fish.

This is what I’d love to see: large studies that compare pregnant/nursing fish-eaters versus pill-poppers. Few researchers have tackled this, in part because we assume DHA works the same no matter how we get it, and because DHA from sources other than pills is difficult to measure or isolate. Interestingly, a study at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health compared height, weight and head circumference results of newborns whose mothers whose main source of DHA was fish versus pills. They found that fish-eaters generally gave birth to larger babies while fish-oil-pill-poppers had newborns with a smaller head circumference.

Is it possible that fish consumption boosts IQ, but fish oil pills do not?

It’s dumbfounding, the difference in results between whole fish and fish oil. The researchers that found negative results of supplementation on nursing infants speculated on what goes wrong. It may be that early intervention with fish oil pills results in an “environmental mismatch” between prenatal and postnatal life,” (e.g. the fetus is “programmed” in the womb to live in an environment without abundant DHA and is thrown off when inundated with these fats later on).

Another theory is that the timing in these recent fish oil pill studies is off. The critical period in which fish oil may influence brain growth may be in the first trimester of pregnancy or toward the end of the first year of life — not during the time periods in which women in these studies were taking fish oil pills. It may be that DHA has a “sweet spot” — an optimum level below and above which may be detrimental to the developing brain. Indeed, when researchers look at fish oil pill supplementation and DHA-deficient premature infants, the results are much rosier.

There’s another compelling explanation of why fish oil pills don’t yield the desired results: DHA doesn’t do its magic alone. Nutrients and proteins in fish and seafood, other than DHA, may be brain-boosters — or at least help us (and our fetuses or babies) to absorb or metabolize DHA better. All the fish oil in the sea can’t compensate for a bad diet.

In the US, a federal advisory recommends that pregnant women not eat more than two servings of fish weekly. This advice may be misguided given that fish such as salmon and sardines are high in DHA but low in mercury. Pop fish oil pills instead; they’re just as good– that’s been the message. But these recent studies point to a different truth.

Thus the case for fish, the whole fish, and nothing but the fish.

Food for thought.

*If you like this blog, click here for previous posts and here to read a description of my most recent book, Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, on the science behind love, sex, and attraction. If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

Do Beautiful Babies Become the Most Beautiful Adults?

Forgive me, I believe my one-year-old is the cutest baby ever. Yes, yes, mothers are biased about their own children. As I detail in my new book, certain reward circuits “light up” in parental brains only when looking at their own offspring. But objectively — objectively! — my daughter is adorable.

The little one has “Gerber baby” features: a bulbous forehead, big eyes, luscious cheeks and thighs (and curls). Babies with these qualities are rated as cuter than those with sunken foreheads, small eyes, and large or long chins. Adults smile and gaze longer at them. Attractive infants are perceived to be more sociable, easier to care for, and more competent than their homely peers. They inhibit aggression in adult men. They receive more nurture.

Our baby thrills to the attention, and my husband and I have started to worry that being cute might not lead to anything good. I have a theory that ugly ducklings and tomboys grow up to have richer inner lives. I don’t want a princess.

We want to know: Do the cutest babies turn out to be the most attractive adults?

Conveniently, a recent study by psychologists Gordon Gallup Jr, Marissa Hamilton, and their colleagues addresses this very question. (I love these whimsical studies; they’re motivated by genuine curiosity.) The presumption is that physical attractiveness remains stable over time. This has been proven in childhood onward: attractive ten-year-olds are likelier to be attractive adults. (Another study found that adult attractiveness can be predicted as early as age five). But until now no study had tracked attractiveness from infancy.

It’s interesting, how the psychologists went about it. They sifted through high school yearbooks and found forty graduating seniors who featured photos of themselves as infants. Then they asked several hundred college students to rate the the individuals — in infancy and in adulthood — for attractiveness.

The upshot?

There was no correlation between attractiveness in infancy and (young) adulthood. Some ugly ducklings turned into swans, some baby swans become ugly ducks. Some gawky, awkward babies remained that way into their senior year of high school. And some beautiful babies kept their glow through the years. This was true of males and females alike. Cuteness — or homeliness — in infancy does not predict future attractiveness.

The study included an interesting side finding: While the raters were likely to agree about which infants were attractive, they often disagreed about which eighteen-year-olds made the cut. Why? The gold standard of baby beauty — the forehead, the eyes, the thighs — is universal. These preferences are hard-wired in us to elicit care and protection, while the perception of adult beauty is tempered by culture.

Cute babies are universal positives. In this light, it’s OK that mine gets attention now. The future will be much less predictable.

*If you like this blog, click here for previous posts and here to read a description of my most recent book, Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, on the science behind love, sex, and attraction. If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

Do You Live Less if Your Mom Was Stressed?

Not long ago, a handful of scientists at the University of California at Irvine were curious about why some people live longer than others — even within groups that have similar ethnic and educational backgrounds, demographic and disease risk profiles, and are exposed to similar stressors in life. At heart, they know the question is impossible to answer. People are complex. The effects of life events on our genes—what we eat, what we breathe, who we love and how well we’re loved, and so on —are impossible to isolate.

Not long ago, a handful of scientists at the University of California at Irvine were curious about why some people live longer than others — even within groups that have similar ethnic and educational backgrounds, demographic and disease risk profiles, and are exposed to similar stressors in life. At heart, they know the question is impossible to answer. People are complex. The effects of life events on our genes—what we eat, what we breathe, who we love and how well we’re loved, and so on —are impossible to isolate.

But the scientists had a hunch that some of us had a bad start —beginning in the womb — because our mothers were highly stressed during pregnancy. There’s an avalanche of evidence that women who are under extreme duress in pregnancy have kids who have shorter attention spans, lower IQ, memory deficiencies, and health problems.

Could prenatal stress also set a baby’s life expectancy clock to tick faster?

One way to find out is to look at the genes of people whose mothers were extremely stressed during pregnancy. In each of our cells are DNA-protein complexes called telomeres, which cap the end of chromosomes. Telomeres are like the plastic bit at the end of a shoelace to keep it from unraveling. Each time a cell divides, they become a little shorter. This makes telomeres something of a longevity marker. People with long tips at the end of their DNA strands tend to live longer than people who have short tips. It doesn’t matter how long your shoelace is; what counts is the integrity of the cap.

In the UCI study, researchers recruited volunteers in their twenties. Some were selected because their mothers experienced a horrid event during pregnancy. The scientists weren’t looking for the normal pregnancy stressors — work-life balance, weight gain, fretting about the baby’s health, and so on. They meant extreme stressors: a sudden divorce, a death in the family, a natural disaster, and physical or emotional abuse.

What they found is disturbing.

Compared to the control group (whose moms had a relatively stress-free pregnancy), people exposed to their moms’ extreme prenatal stress had significantly shorter telomeres. By our mid-twenties, most of us lose about 60 base pairs of telomere length annually. Not so of people who were exposed to extreme prenatal stress — they lose drastically more telomere length each year. The men had 178 fewer base pairs on average (equivalent to 3.5 additional years of aging). Women had a shocking 295 base-pair deficit (5 years of accelerated aging). It seems that a mother’s prenatal stress hits her daughter harder than her son.

How does this happen? During pregnancy, stress may alter blood flow, oxygen, and glucose metabolism between mother and baby. High levels of the stress hormone cortisol from the mother flood the placental barrier. Excess cortisol may also slow down in the production of telomerase, an enzyme that acts as a repair kit for telomeres. Telomerase adds telomeric DNA to shortened telomeres. It regenerates our cells and tissues. Like a fountain of youth, telomerase gives back what time takes away.

So what if you’re on a telomerase-less trajectory?

Here’s the big relief: Your clock doesn’t have to keep ticking so quickly, even if it has been set that way before birth. There’s strong evidence that lifestyle changes can amp up telomerase production. One study found that stress management, counseling, and a healthy diet are associated with higher telomerase activity. Another found that meditation turns up the telomerase dial.

In the research community there’s much interest in the idea that, by maintaining our telomeres, gene therapy might someday reverse or prevent aging if started early enough. Is it possible? As a measure to conceal the abuses of youth, teens could freebase on telomerase.

Oh, the ways to stress out Mom.

*If you like this blog, click here for previous posts and here to read a description of my most recent book, Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, on the science behind love, sex, and attraction. If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

Assorted Trifles (from the science of love, sex, and babies)

Research is like a box of chocolates; you never know what you’re going to find. An assortment of studies on love, sex, and babies — fresh from the lab.

Research is like a box of chocolates; you never know what you’re going to find. An assortment of studies on love, sex, and babies — fresh from the lab.

Scientists found that men whose ring fingers are longer than their index fingers are likelier to have longer-than-average penises, at least among Korean men whose flaccid genitals were stretched under anesthesia. Studying the files of women who were raped in 1999-2006, French researchers discovered that there were fewer incidences of living sperm than in rape victims in previous generations, which supports the theory that sperm quality is declining. Women are likelier to get pregnant if they ovulate from their right-side ovary, visible by ultrasound, especially after two consecutive left-side cycles, inspiring women undergoing fertility treatment to desire a L-L-R pattern. Among women whose fetuses inexplicably died in third trimester, 64 percent (392/614) had a premonition before their doctors told them. They described a feeling of discomfort, of a strange unease; that they understood subconsciously that the baby would die. Many described how they dreamed of dead relatives and of death on the night the baby probably died. A recent fMRI study reported that women who had given birth vaginally exhibited greater activation in brain regions involved in the regulation of empathy, arousal, motivation and reward circuits in response to their baby’s cries compared to those who had not. Women who snore loudly and frequently were at high risk for low birth weight (relative risk = 2.6 [95% confidence interval = 1.2-5.4]), and fetal-growth-restricted neonates. The success of an IVF transfer may in part be predicted by how much glucose medium an embryo “eats” on days 4 and 5. On Day 4, female embryos consume significantly more sugar than males.

Publishers Weekly — First Review for Chocolate Lovers!

My first review for Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?, from this week’s Publishers Weekly.

My first review for Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?, from this week’s Publishers Weekly.

—-

Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies: Exploring the Surprising Science of Pregnancy

Jena Pincott. Free Press, $15 trade paper (256p) ISBN 978-1-4391-8334-2

Science writer Pincott (Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?) began her research when she was pregnant; her daughter was born during the writing process, and she describes the work as “curiosity -driven,” urging readers to flip to the pages that interest them most. As Pincott negotiates her pregnancy, she explores a wide array of subjects expectant parents will find utterly captivating, drawing from studies in evolutionary psychology, biology, social science, neuroscience, reproductive genetics, endocrinology, and largely from research in the field of epigenetics, the influence of environment on the behavior of genes. She examines each phase of her own pregnancy, addressing odor and taste aversions (the “gag list”), vivid dreams, how diet affects a gene’s behavior, and a wealth of other subjects. She delves into how dads react to pregnancy (many put on weight) and makes the remarkable observation that what grandma ate when pregnant way back when may influence the baby’s future health (“I’m eating for two generations,” she quips). While readers will be entertained and fascinated by this text from start to finish, the concluding chapter, “Lessons from the Lab,” offers expectant mothers a valuable summary of practical research-based tips (moderate stress experienced by mom may actually be good for the fetus; eating a chocolate bar a day may improve baby’s temperament). Pincott writes with humor and vibrancy, bringing science to life.

Do Fish and Coconuts Reverse Prenatal Stress?

Is it any coincidence that the most laidback people I’ve ever met hail from Brazil, land of fish and coconuts?

The mellowness of Brazilians came to mind when I read a study on prenatal stress to be published next month in the International Journal of Neurodevelopmental Medicine. The researchers, including lead author Carlos Galduróz, are biologists at Universidade Federal de São Paulo (in Brazil).

It’s been long known that significant prenatal stress — characterized by a blitz of the stress hormone cortisol — harms a fetus. Prenatal stress results in an increased risk of premature birth and low birthweight. In humans, it’s linked with anxiety, attention deficit disorder, impaired memory, low test scores in childhood, and depressive behavior in adulthood. Rats whose mothers are exposed to extreme stressors are likelier to have impaired motor skills and are slower to learn.

Intriguingly, there’s evidence that the mother’s diet might offset some of these disadvantages. A baby whose stressed-out mom ate “special” foods during pregnancy and lactation may fare better than one whose equally stressed -out mom ate a normal diet.

Galduróz and his colleagues were curious to know if the composition of fat in a prenatal diet might make the difference. So, during the equivalent of second and third trimester, they subjected some of the rats in their study to extreme stress — restraint and bright lights for forty-finve minutes, three times daily. Some of these pregnant rats were fed a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids, the kind found in salmon, sardines, and other fish. Others were fed a diet high in saturated fatty acid from coconut milk. A third group ate normal rat chow.

The results?

As expected, babies of stressed-out moms had lower birth weights. The surprise came three weeks later: Babies whose moms ate fish oil or coconut fat diets during pregnancy and lactation gained weight quickly. So quickly, in fact, that they became the same weight as the babies whose moms weren’t stressed during pregnancy. In other words, fish and coconut fats reversed the impact of low birthweight, a potentially dangerous effect of prental stress.

That’s not all.

Babies exposed to prenatal stress were more active (restless) than other pups if their moms were on a regular or coconut-oil diet. Interestingly, if a stressed-out mother was on a fish oil diet, her pups were not more restless than those of pups with non-stressed moms.

In an earlier study by the same authors, adult rats whose moms ate a coconut fat or fish oil-based diet released fewer stress hormones (a reduced corticosteroid response) than rats whose moms ate a normal diet.

Many studies have shown that fish oil, omega-3s, modulate mood by reducing the stress response. This has been shown in rat studies, and also in many (but not all) human studies. Is it possible that when a mother consumes food containing omega-3s, her babies are less agitated? Are they happier? Of course, rodents express anxiety, neuroticism, and depression differently from human babies. But the healing effect of nutrients is fascinating. Do stressed-out moms on fish-and-coconut diets have happier, healthier babies than their equally stressed peers who don’t eat as well?

For the real possibility that fish and coconut oil have prenatal physical and psychological perks, I link to a favorite recipe here. It’s for moqueca, a stew made of fish and coconut fats, from Bahia, the Coconut Coast of Brazil.

*If you like this blog, click here for previous posts and here to read a description of my most recent book, Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, on the science behind love, sex, and attraction. If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies?: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

Do Flame Retardants Make Us Dimmer?

When I was in the second trimester of pregnancy, my husband and I bought a new king-sized mattress. Like all cotton mattresses sold in the U.S., ours had been treated with a flame retardant containing polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and/or organohalogen compounds (OHCs). Flame retardants are also in pillows, car and airplane seats, drapes, rugs, and insulation. They’re in electronic equipment, like TVs, and in the dust on top of TVs. They’re in air and soil and breast milk. Almost all humans have flame retardants flowing through their veins.

Around the same time I got my new mattress (on which I tossed and turned in third trimester), two surprising studies were published on the effects of flame retardants on fetuses and young children.

A group of researchers at the University of Gronigden in the Netherlands recruited nearly 70 pregnant women in third trimester, taking samples of their blood and measuring it for PBDEs and OHCs. Five years later, the children were given standardized developmental tests for motor skills (balance and coordination), cognition (intelligence, spatial skills, control, verbal memory, and attention), and behavior.

The result: PBDEs were correlated with worse performance on fine motor tasks and a shortened attention span. Strikingly, they were also linked with better coordination and visual perception, as well as better (more placid?) behavior. OHCs, meanwhile, were correlated with worse fine motor skills. Oddly, these kids had better visual perception.

Researchers at Columbia University tested for PBDEs in the cord blood of nearly 400 women who delivered their babies at a New York City hospital. These children were given mental and motor development tests in infancy and, later, at four-to-six years. These tests measure memory, problem solving, habituation, language, mathematical concept formation, and object constancy. They also assess ability to manipulate hands and fingers and control and coordinate their movements.

The result: At both age intervals, children who had higher cord blood concentrations of PBDEs scored significantly lower on tests of mental (lower IQ) and motor development. This was particularly evident at age two for motor skills and age four for IQ (nearly 8 points lower for certain PBDEs).

Are flame retardants slowing us down? Correlation is not causation, but there’s a real risk that they do — and researchers have some ideas about how these chemicals have a toxic effects on the brain. OHCs (for instance) have been found to decrease a fetus’s production of thyroid hormone by interfering with thyroid receptors. This leads to an increase in thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Brain development in the fetus relies on the precise timing and quantity of thyroid hormone; too much or too little causes developmental delays. High prenatal exposure to TSH is associated with lower IQs – 4 points less on average. During critical developmental periods, PBDEs and OHCs may also have a toxic effect on neurons in the hippocampus, the memory region of the brain, by reducing the number of neurotrasnmitter receptors.

Infants and toddlers have what researchers call a high “body burden” of flame retardants. Household dust, which floor-playing infants and toddlers encounter constantly, accounts for 80-93 percent of postnatal PBDE exposure, followed by breast milk (however, the benefits of nursing appear to outweigh this drawback; breastfed babies score higher on neurodevelopmental tests).

A disturbing fact is that American kids have levels of PCBEs that are 10 to 1,000 times higher than their peers in Europe or Asia. We produce 1.2 billion pounds of the stuff annually. (Interestingly, the Scandivanian study, whose subjects had lower levels of prenatal exposure, found no IQ deficit while the U.S. study did.) Consider our nation’s problems: attention deficit disorder, placidity, lower standardized test scores in reading and math.

Are flame retardants making kids dimmer?

The question fires up the imagination. Should pregnant women be advised to avoid, say, dusting and buying new mattresses in the same way we avoid emptying the litter box (to avoid toxoplasmosis)? Are the perceived gains in visual perception real, and, if so, why, and do they come at the expense of other abilities? Are urban kids at a higher risk than average? Are there naturally flame-retardant materials that we can use in lieu of chemicals? More research, especially on American kids, is warranted.

After all, the nightmare scenarios can keep an expectant mom up all night, tossing and turning on her nonflammable mattress.

* If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

WAAROM VROUWEN CHOCOLA LEKKERDER VINDEN DAN SEKS

The new Dutch mass market edition of Blondes (retitled, in loose translation, “Why Women Prefer Chocolate to Sex”)

The new Dutch mass market edition of Blondes (retitled, in loose translation, “Why Women Prefer Chocolate to Sex”)

The Real Purpose of Eyebrows?

Human faces are relatively flat. Alas, evolution has flattened the jutting jaw and the bulging brow ridge.

Fortunately, we still have one reliable landmark: the eyebrow.

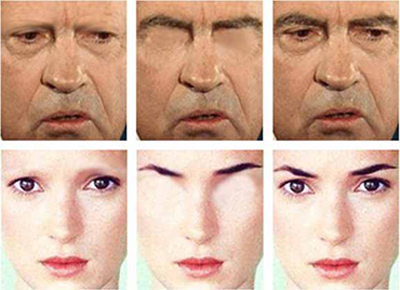

According to a study by MIT behavioral neuroscientist Javid Sadr and his colleagues, eyebrows have remained because they are crucial to facial identification. Faces without eyebrows are like land without landmarks.

The study: Volunteers were asked to identify fifty famous faces, including that of former U.S. president Richard Nixon and actor Winona Ryder. The photos were digitally altered and displayed either without eyebrows or without eyes. When celebrities lacked eyes, subjects could recognize them nearly 60 percent of the time. However, when celebrities lacked eyebrows, subjects recognized them only 46 percent of time.

The lesson: eyebrows are crucial to facial identity — they’re at least as important as your eyes, if not more so. If you put colored contacts in your eyes, pumped collagen into your lips, or put on a pair of funky sunglasses, people would probably still recognize you easily. But try shaving off your eyebrows. Chances are that everyone will say they didn’t recognize you at first glance.

As Sadr points out, eyebrows pop out against the backdrop of your face — and for that reason not only identify who you are but how you’re feeling. Along with the lips, they may in fact be the most expressive part of your body. The single raised eyebrow is a universal sign of skepticism, and the dual raised eyebrow a sign of surprise.

The shape of your eyebrows also reveals, in a glance, a lot about your age and other characteristics. Bushy, gnarly, salt-and-pepper brows: older apha males. Thin, graceful arcs: young, stylish women. Sparse, light brows: youths. Waxed and tweezed, the brow can advertise good grooming.

Eyebrows sometimes meet each other halfway across the bridge of the nose, especially on men, to form a monobrow, which resembles the vanished browridge of our primate ancestors. Distinctive? Yes, and also brow-raising.

*This entry was previously published on this blog. If you wish, also check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies: The Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

Are Extroverts That Way Because of Their Fathers?

All babies demand their parents’ attention. But how many 11-month-olds demand the attention of strangers, too? Ours does. We bring her to restaurants and she scans the room until she catches someone’s eye. My husband will pick her up and carry her over to her admirer, whom he’ll chat up. Dad’s a socialite, Baby’s a socialite. Mom reaches into her bag and pulls out a book.

You might think your baby’s social confidence depends on the usual mix of genes and environment. This is true, but it might not be the whole truth. There’s also evidence that children rely more on their father’s social signals than their mother’s. That is, socially confident dads may have more socially confident kids. Socially anxious fathers may have more socially anxious kids. It matters less whether Mom is a social butterfly or a bookworm.

The bulk of the research on paternal influence on sociability comes from Susan Bogels, a professor in Developmental Psychopathology at the University of Amsterdam, and her colleague Enrico Perotti. In a recent review, Bogels and Perotti draw on research that suggests a dominant paternal role in their children’s sociability, including:

• In one study, 9-11-year-olds were asked to imagine themselves in a series of stories involving strangers, while their mother and father responded in a socially anxious or socially confident way. Children who had socially anxiety were more influenced by their father’s reaction more than their mother’s.

• A study of boys with behavioral problems, including social anxiety, found that fathering, but not mothering, predicted the children’s level of inhibition. In another study, secure infant-father attachment, but not infant-mother attachment, predicted stranger sociability among toddlers.

• Among kids enrolled in treatment for social anxiety, those whose fathers had high levels of social anxiety had a worse outcome (were more socially anxious) than those whose mothers had it. Socially anxious mothers are not as likely as socially anxious fathers to make their kids less sociable.

So here’s the mystery: Why would fathers, who have less to do with childrearing than mothers, have more influence on their children’s sociabilty?

It’s an interesting question, and Bogels and Perotti have an interesting answer. “In the course of human history,” they write, “fathers specialized in external protection (e.g. confronting the external world outside the clan or extended family), while mothers provided internal protection (e.g. providing comfort and food). Therefore, children may be hardwired to respond more to their father’s signals about the social world than the mother’s, and adjust their behavior accordingly.

Through the ages, it benefited children to rely more on their father’s than mother’s cues about whether unfamiliar people are generally hostile or cooperative. Of course, gender roles have long since changed – moms go out into the world every day and meet strangers – but our instincts haven’t.

So the lesson here is that fathers orient their children outward, mothers inward. When researchers observed a group of toddlers taking swimming lessons, they took note of where the parents stood. Mothers protectively stood in front of their babies, encouraging face-to-face interaction with them. Fathers stood in back, so that their children would face their social environment.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

Bogel and Perotti’s review includes a fascinating aside about paternal roughhousing and its effect on children’s social confidence. Rough-and-tumble play – I think of my husband tossing our infant in the air, spinning her around, throwing her over his shoulder, as she giggles and squeals- gets a scientific seal of approval.

Here’s why. Kids learn to associate physiological arousal – a racing heart, tight chest, spinning head – with fun instead of fear, which crosses over into other social interaction. Roughhousing also involves behavior – being aggressive, sneaky, teasing, playful – that requires different roles and different responses, and forms a basis for social skills. By pinning kids to the ground, swinging them like sacks of potatoes, attacking them and getting attacked – fathers make their progeny more confident.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

So many questions. If we have evolved so that fathers strongly influence their children’s sociability, what does this mean?

It means that fathers who are socially anxious themselves are likelier to have kids who are not socially confident. If a kid suffers from severe social anxiety, perhaps his or her father should be involved in the kid’s therapy or get therapy himself. But what about kids who don’t have fathers who are involved or live at home? How do mothers compensate? And what about gender? So far there is no evidence that boys are more susceptible to the father’s signals than are girls, but is this really so? And what about other male figures – male teachers, older brothers, uncles, grandfathers – are they equally influential? At what age is paternal influence on sociability strongest? And are paternal genes more influential here too?

Further research is warranted. Until then, we can wonder about the great socialites in history – the Jackie Os, Andy Warhols, Paris Hiltons, Truman Capotes, Gloria Vanderbilts, Nan Kempners, and Ivana Trumps. Did they get it from their dads?

Are Men Likelier to Cheat When Their Partners are Pregnant?

It’s bad enough that Congressman Anthony Weiner had been taking photos of his naked self and sending them to women who weren’t his wife. It’s worse when we learn that his wife is three months pregnant.

Aha, that it!, some cynics claim. Now that Weiner’s oats are sowed, he’s exploring new (and, if the twittering teen rumor is real, very green) pastures. It’s only natural.

But is it? Are men really more likely to cheat when their wives are pregnant?

Turns out, the answer is that it depends on the man.

Reviewing the studies of pregnancy and sex, it seems there are three categories of expectant fathers.

- Type Z cheats or wants to cheat (the Weiners).

- Type Y desires his pregnant wife more than ever.

- And then there’s Type X — a man who has a decreased sex drive and a lower risk of cheating on his wife.

The bad news is that at least one study found that, yes, the risk of a given man to cheat on his wife increases during pregnancy, even if he is otherwise satisfied in his marriage. His reasons? He may feel ambivalent about the pregnancy or the changes that go with it. His partner, especially in her first and third trimesters, may not feel like having sex. Her sex drive may diminish. She may think her body is unattractive.

(Incidentally, bodily dissatisfaction happens to be the number one reason why most women have less sex during pregnancy. Most of us think pregnancy is a turn-off for men. That’s a misconception.)

But here’s the good news for pregnant women. Fact is, many men — the majority as found in this study — desire their pregnant partner even more over the course of the pregnancy, even if they aren’t having as much sex as before. They find her as physically attractive as she was prepregnancy, if not more so. These are usually the Type Y guys. Another study found that, while couples had sex less frequently in third trimester, the only circumstances under which men change their sexual behavior is if they are older or worried about the safety of the fetus. (Note: Sex does not raise the risk of miscarriage in pregnancies that are not high risk.) Otherwise, men desire sex with their wives just as much.

From an evolutionary perspective,this makes some sense. Women benefited from having their mates around to help support them through pregnancy and childrearing. Sex helps men stick around.

The Type X expectant father – the one with a low sex drive and a lower risk of infidelity – may overlap with Type Ys. These are men who, at some point over the nine months, are afflicted with pregnancy symptoms: nausea, weight gain, mood swings, fatigue, even vomiting. Hormones are the culprit. These men have higher levels of prolactin, a hormone associated with sluggishness, weight gain, and bonding and parental behaviors. Their testosterone levels plummet, making them less combative and sexually aggressive.

There’s an upside to Type Xs. It turns out that these faithful, fattening men display the most fatherly behavior when the baby arrives. As new dads, they’re more likely to hear and respond to their infant’s cries. They’re more compassionate and tolerant. They make better fathers.

One might speculate that Weiner’s Type-Z behavior while his wife is pregnant doesn’t bode well for Weiner’s fathering instincts. It’s clear that if any hormone is raging in the man, it’s testosterone — not prolactin. He is probably not sharing his wife’s morning sickness and taking turns with her over the toilet.

There’s no crime in what Weiner has done; he’s just another politician more interested in power more than paternity. But he is making us a little nauseous.

*If you like this blog, click here for previous posts and here to read a description of my most recent book, Do Gentlemen Really Prefer Blondes?, on the science behind love, sex, and attraction. If you wish, check out my forthcoming book, Do Chocolate Lovers Have Sweeter Babies: Exploring the Surprising Science of Pregnancy.

Eternal Sunshine of the Springtime Mind

Warm weather isn’t just good for the flowers. Sunny days have been linked to higher stock returns, and touching a warm object can make people more generous. My article in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal.

Warm weather isn’t just good for the flowers. Sunny days have been linked to higher stock returns, and touching a warm object can make people more generous. My article in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal.

Where Do Demanding, Unweanable Babies Come From?

A season ago, when my daughter reached the six-month mark, her pediatrician told us to introduce her to a new food every few days and see what she likes. It wasn’t time to wean her, but soon it will be, and supplementation should help the transition. So I lovingly shopped for organic fruits and vegetables: apples, bananas, avocados, peas, and so on. I presented them passively — as items for her to experiment withon her placemat — and actively, by making mmmms, playing airplane, and swallowing the goop and showing her my tongue.

A season ago, when my daughter reached the six-month mark, her pediatrician told us to introduce her to a new food every few days and see what she likes. It wasn’t time to wean her, but soon it will be, and supplementation should help the transition. So I lovingly shopped for organic fruits and vegetables: apples, bananas, avocados, peas, and so on. I presented them passively — as items for her to experiment withon her placemat — and actively, by making mmmms, playing airplane, and swallowing the goop and showing her my tongue.

Three months later, we’ve made astonishingly little progress on the solids front. At best, the infant deigns to nibble delicately on peas and lentils. She’ll squish the bits of mango and avocado on her plate and drop them on the floor. She’ll taste a food then whip her head to the other side and bat away the spoon. She wrinkles her nose.

All she really wants to do is nurse. Baby loves to nurse. She cries and cries in the wee hours of the morning because she wants to nurse. She is tall and heavy for her age.

Who’s to blame (at least in part) for her unweanable stubbornness?

Her dad.

It’s not only convenient to blame the father for babies who won’t give up nursing, It’s scientific. There’s evidence.

Here’s how it works, according to a new study Bernard Crespi, an evolutionary biologist at Simon Fraser University. How much and how long a baby nurses depends in part on her genes. The genes she inherits from her father have an ulterior motive. Paternal genes want the baby to extract as much as possible from the mother.

Paternal genes are thought to influence:

- suckling strength (so the baby extracts as much milk as she can)

- tongue size (a larger tongue is a better suction pump)

- crying (for maternal attention and food)

- appetite and speed of eating

- duration of breastfeeding before weaning

- night-time suckling (results in suppression of periods, which helps delay future pregnancies/siblings)

The genes that influence these behaviors are active only when they come from the dad. This is called genetic imprinting — when only the genes from one parent are expressed. Dad’s genes strongly affect the intensity of infant behavior. Only a tiny percentage of human genes are imprinted.

Dad’s genes are greedy for a good reason. From a biological perspective he has nothing to lose by making sure this particular offspring who carries his genes demands a lot of her mom — including suckling often, crying a lot, and taking a long time to wean. This behavior may be essential to a child’s survival in a setting in which resources are limited. “Weaning” genes have been shaped this way under evolutionary pressure in a premonogamous era.

Mom’s genes, meanwhile, are more moderate. They want the child to survive but dial back the feed controls. They’d prefer for a baby to self-feed and start solids sooner. Mom’s genes push moderation to save resources (time and energy) for her other (or future) offspring. When paternal genes are disabled and maternal genes are active, babies have Prader-Willi syndrome, a condition that manifests as inability to latch and suckle effectively, complacency, and lack of crying or other solicitation for food. These infants wean early because they never really nurse. They fail to thrive.

Demanding, unweanable infants come from dads. At a minimum, paternal genes play a real role in their aggressive eating, crying, and nursing behaviors.

Now that they’re outed, perhaps guilty fathers should be the ones to work the night shift and scrape food off the floor?

How big is your limbal ring?

Of all the qualities that give an attractive person an edge, here’s one you’ve likely overseen: the limbal ring, the dark circle around iris. The limbal ring is the line that separates the colored part of the eye from the white (the sclera).

It’s completely unconscious, the way we all judge others’ limbal rings. In the 20 milliseconds or so it takes to assess a person’s attractiveness, you’re factoring in the size and shade of the limbal rings. The bigger and blacker they are, the more attractive the eyes. People with the prettiest eyes have the most prominent limbal rings.

This, anyhow, is the upshot of a recent study by Darren Peshek and his colleagues at the Department of Cognitive Science at the University of California at Irvine. The researchers showed volunteers eighty pairs of male and female faces. Each pair of faces was identical except the eyes: one had dark limbal rings and the other had no limbal rings. The volunteers were asked to pick which face was more attractive and to indicate their degree of preference.

Men thought women with the dark limbal rings were more attractive than those without, and women thought the same of men with dark limbal rings. Men and women also judged faces of the same sex as more attractive when the limbal rings were large.

Looking into my baby daughter’s eyes, I see the blue of her iris is framed by a thick black limbal ring. The contrast makes the white of her eyes so white they look blue. The very young have the thickest, darkest limbal rings.

Which is exactly the point. The limbal ring serves as an honest signal of youth and health-desirable qualities, reproductively speaking. The ring fades with age and with medical problems. It’s thickest from infancy through the early twenties. A thick, dark limbal ring may make us appear younger. It makes the whites of the eyes whiter. This might be why so many people think light eyes are so sexy: the limbal ring, when present, shows up more.

There are so many ways to fake the appearance of youth. You can wear makeup and wigs and get tummy tucks, plastic surgery, Botox, and boob jobs.

But a fake limbal ring?

Yes, this too.  Long ago, Japanese schoolgirls discovered the edge a limbal ring can give you by wearing “limbal ring” contact lenses. They make the eye look bigger and more defined. And while you’re eyeing these contacts, you might as well buy a set that expands your pupils too. Big, dark, dilated pupils signal emotional arousal. They, too, act on the unconscious favorably.

Long ago, Japanese schoolgirls discovered the edge a limbal ring can give you by wearing “limbal ring” contact lenses. They make the eye look bigger and more defined. And while you’re eyeing these contacts, you might as well buy a set that expands your pupils too. Big, dark, dilated pupils signal emotional arousal. They, too, act on the unconscious favorably.

The limbal ring is well-named. Limbis means border or edge, and it’s related to limbic, meaning emotion or drives. The limbal ring, seen from inches away, is an intimacy zone. Don’t flirt until you see the whites of their eyes.

Why are Redheads More Sensitive?

Redheads may be hotheads, but they get colder faster. They also bruise more easily. And they feel more pain.

All this comes from a series of studies done in the last few years on people with genes for red hair. A true redhead produces an abundance of a yellow-red pigment called pheomelanin. (Brunettes produce the more common eumelanin, a dark brown pigment.) A redhead’s prodigious pheomelanin output is the result of mutations, or variants, of the MC1R.3 gene. Redheads have two copies of this variant allele, one from each parent.

So what does this “redhead gene” have to do with sensitivity? The same gene is involved in the body’s perception of pain. Edwin Liem, an anesthesiologist at the University of Louisville, suspects that when both copies of the MC1R.3 gene are variants, as they are in redheads, receptors in the nervous system modulate pain more intensely. It’s also possible, according to Liem, that the redhead version the MC1R gene also directly affects hormones that stimulate pain receptors in the brain.

In one study, Liem and his colleagues compared the pain tolerance of sixty naturally red-haired volunteers with sixty brunettes. The redheads reported that they felt a chilling pain at around 6 degrees C (43 degrees F), unlike the volunteers with dark hair. Brunettes did not feel an aching chill until the temperature approached freezing.

In another experiment, also led by Liem, women with various hair color types were exposed to electric shock. Turns out, the redheads needed about 20 percent more anesthetic to relieve the pain (confirming the common belief among anesthesiologists that redheads are tough to knock out). While redheads have normal blood counts and coagulate blood the same as anyone else, they bruise more easily. Yet another study found that redheads are more than twice as likely as women with other hair colors to fear and avoid the dentist.

These studies have been done on women only, and it’s unknown whether red-haired men would have the same outcome. (However, there’s evidence that pain pathways differ between the sexes.)

Redheads are stereotyped as being hot-headed, tempestuous, dramatic, high-strung. Is it possible that a genetic sensitivity to pain can affect temperament? It’s fun to speculate. For some, physical pain may translate into emotional pain. Sensitivity may tip over into volatility. Could a fiery, short temper even be a pain avoidance mechanism? Why not–after all, a good offense can be the best defense.

Why are Men Mad About Mammaries?

Let me count the theories:

1. Freudian (breasts remind men of their moms and the nurturing of childhood)

2. Evolutionary (breasts resemble buttocks, and prehuman ancestors always mounted from behind)

3. Reproductive (breasts are an indicator of age, and big breasts in particular are a marker of high estrogen levels, associated with fertility).

Do these reasons sufficiently explain why breasts are beloved — even in cultures that don’t eroticize them any more than the face?

If not, here’s another:

Breasts facilitate “pair-bonding” between couples. Men evolved to love breasts because women are likelier to have sex with — and/or become attached to — lovers who handle their breasts.

This idea came up in New York Times journalist John Tierney’s interview with Larry Young, a neuroscientist famous for his research on monogamy. According to Young, “[M]ore attention to breasts could help build long-term bonds through a ‘cocktail of ancient neuropeptides,’ like the oxytocin released during foreplay or orgasm.”

The same oxytocin circuit, he notes, is activated when a woman nurses her infant.

When women’s breasts are suckled, as they are during breastfeeding, the hormone oxytocin is released. Oxytocin makes the mother feel good and helps her bond with her baby. She feels loving and attached. The same reaction might happen if a man sucks and caresses a woman’s breasts during foreplay. In our ancestral past, the most titillated men may have been the ones to attract and retain mates and pass on their genes.

The “boobs-help-bonding” theory may not be the strongest explanation of why men love breasts, but it’s worth introducing to the debate. That said, there are many ladies out there for whom a lover’s suckling does nothing — and there are many breast-ogling boobs who know nothing of foreplay.

What Singles Can Learn from Baby Talk

When you become a new parent you get a lot of advice on how to connect with your infant. To win her over, you’re told, talk the way she talks. If Baby says “bah-bah-bah,” you say, “bah-bah-bah” back. You can make your “bah” sound like a real word by saying BAH-tel” or “BAH-th.” The content doesn’t really matter. You just need make sure you sound like her. Researchers call this “language style matching.” It draws the infant in and helps her connect with you. Experts can predict a baby’s attachment to her mother by how much they bah-bah back and forth during baby talk.

When you become a new parent you get a lot of advice on how to connect with your infant. To win her over, you’re told, talk the way she talks. If Baby says “bah-bah-bah,” you say, “bah-bah-bah” back. You can make your “bah” sound like a real word by saying BAH-tel” or “BAH-th.” The content doesn’t really matter. You just need make sure you sound like her. Researchers call this “language style matching.” It draws the infant in and helps her connect with you. Experts can predict a baby’s attachment to her mother by how much they bah-bah back and forth during baby talk.

Singles seeking love and connection can learn from this, according to a new study led by James Pennebaker and Molly Ireland at the University of Texas at Austin, and their colleagues at Northwestern University. What the psychologists investigated is whether people on a first date who use similar words hit it off better than those who don’t. Could language style predict whether you and your date will decide to see each other again and even have a strong and stable relationship eventually?

To find out, the researchers recorded college students on speed dates. Thrown together for four-minute pairings, the men and women warmed up by asking each other the usual questions: Where are you from? What’s your major? How do you like college?

Using a computer algorithm to analyze the speed-daters’ conversations, Pennebaker and Ireland found that men and women that wanted to see each other again matched each other’s function words significantly more often than those that had no interest in each other. Function words are like glue. They are not nouns or words; rather, they show how those words relate. They are words like the, a, be, anything, that, will, him, and well. They are the yeses and okays and the pauses and interjections between words. They are the ifs, ands, and buts. By themselves they don’t sound like much, but they set a mood.

The more a couple’s language styles matched, especially the function words, the likelier they were to hit it off. Couple whose speaking styles were in sync more than average were nearly four times as likely to desire a second date as those that were not. About 77 percent of similar-sounding speed-daters desired a second date compared to only about half the dissimilar speakers. Similar-speakers were also significantly more likely to be dating three months later.

Language style matching is usually unconscious, according to the researchers. It’s verbal body language. Just as couples on the most successful dates make more eye contact, lean in toward one another, and otherwise echo each other’s body movements, they also echo each other’s choice of words. We put ourselves in sync with people with whom we want to get close and stay close.

Pennebaker and his team also used the alogrithm to test written correspondence for language style, and found that couples who had been dating a year or more were likelier to stay together if their writing styles in text messages matched.

You can predict if you and your date or partner are in sync by taking Pennebakers’s online test at http://www.utpsyc.org/synch/. Enter your and your love’s email or text correspondence and you’ll get a number that assesses how much your language matches up — which in turn may predict how well your relationship will hold up.

**

If you and your partner use actual baby talk to communicate — that is, speaking in a high-pitched voice with elongated syllables to your ickle-bitty-peshus wuv –you may have an especially healthy long-term relationship. According to a study by researchers Meredith Bombar and Lawrence Littig, baby talk helps lovers enhance feelings of mutual intimacy and attachment to each other. Compared to other couples, babytalkers are more secure and less avoidant in romantic relationships.

Why? In effect, baby talk, when mutual, is not only a form of language style matching but also a way to reactivate primal circuits of attachment. It taps into the unconditional love of a parent for child.

The old “play” circuits are activated; as in any form of fantasy, baby talk allows a couple to step outside the limits of self, space, and time. Stress is reduced — the same reason why a recent study on light S&M found that couples who spank together stay together. Babytalking lovers get a blast of dopamine and oxytocin in areas of the brain involved in reward and bonding — the ventral tegmental area, orbitofrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex.

Mutual use of high-pitched voices, soothing whispers, cooing, lisping, and making expressive faces is also a way of “looping” or “mirroring” affection. Along with the other bonding benefits, baby talk may be a way of flaunting one’s healthy emotional neural circuitry — suggesting not only love and commitment but also strong nurturing instincts.

Do babytalking couples make better parents? Who knows — but secure, loving, long-term ones do.

Do Brothers Stall Their Sisters’ Sex Lives?

Nearly eight months ago I gave birth to a baby girl. The child is now a seam-popping twenty-plus pounds. Infants, they grow so quickly it’s creepy — my thoughts fast-forward through her teething years to the teens, and I’m terrified. Problem is, my family lives in New York City where children want to be adults. The weenies of tweens should stay in their jeans, but all too often they don’t.

The onset of girls’ sexual maturity depends a lot on the social environment — peers, culture, and so on. A recent study by Australian behavioral ecologists Fritha Milne and Debra Judge found that it especially depends on the family environment, and not in the expected ways of curfews and chastity pledges. Sure, if you’re a teenage girl your parents might hold you back from trying to lose your virginity. So may your grandparents and any other authority figure in your family.

But so might your little brother.

Milne and Judge recruited nearly two hundred women and seventy-six men, all living in or around the city of Perth, Australia, and asked them questions about their family lives and sexual development. The results were that girls with only younger brothers lost their virginity an average of more than a year later (at age 18.3) than girls with younger sisters only. Girls with both younger brothers and sisters lost it nearly two years later on average (age 19.3) than girls with no younger siblings. Younger sisters alone had no impact.

The chastity effect only applied to girls with younger brothers. Having a big brother (or sister) didn’t make a girl any less likely to hold onto her virginity, yet another strange pattern emerged. This one involved the girls’ physical maturity.

The more older brothers a girl had, the later she got her first period. Girls with only elder brothers got their first visit from “Aunt Flo” up to a year later (at age 13.6) than girls with older sisters or no older siblings (age 12.7). (This is meaningful given that breast cancer and other conditions are related to earlier menstruation.)

Elder brothers delay physiological maturation, while younger brothers delay behavioral maturation.

What’s going on?

Trained as behavioral ecologists, Milne and Judge took a look at the big picture. Daughters are often caregivers. Historically, as has been found in traditional societies, a woman with daughters as first- or second-born children has a larger family than a mom whose first children were sons. Elder daughters take care of younger siblings, which frees up Mom to keep popping them out. Boys historically required more resources than do girls, which made big sister’s contributions even more important. As a result, these helpful elder daughters experience a delay in starting their own families. In the modern world where women don’t usually start their families until their mid-twenties on average, this is no problem, but in the past females with brothers may have had fewer children over their lifetimes.

The bigger mystery is what’s actually behind Big- and Little Brother’s stalling effect on their sisters’ sexuality. This is unknown territory, so Milne and Judge tread lightly here. The safest theory is that the delays are behavioral. Girls with little brothers lose their virginity later because they’re too busy taking care of their siblings to have love lives of their own. Perhaps little brothers, who are slower than female siblings to develop and reach puberty, keep their elder sisters in a more childish mindset. Or perhaps the stress of care-giving slows down puberty.

The researchers should also consider a much more surprising yet equally plausible theory: brothers send out chemical cues (pheromones) in their sweat that inhibit their sisters’ sexual development. Odd as it sounds, this would explain the perplexing finding that girls with older brothers get their first periods later than their peers. And, it appears, so do girls who grow up with their biological fathers in the household, compared to their peers with absent dads. Several studies, including here and here and a large one at Penn State that involved over nineteen hundred college students, came to this conclusion. (Interestingly, the same study found that girls growing up in homes with males unrelated to them got their periods earlier than average.)

The sweat-stifles-sexuality theory isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. Other animals — rodents, for instance — use pheromones to modulate sexual maturity and fertility in a population. Over the years, a girl would inhale chemical cues in fraternal sweat — think of all those sock and armpit odors. Those chemicals would hit the hypothalamus of her brain where sex hormones are produced, and slow down the works. Puberty strikes a little later. Evolutionarily speaking, the result is that a girl could stay in the family nest longer without conflict. The risk of incest is reduced.

So should I try for son now? Truth is, the data applies to populations, not individuals. There are no guarantees; these are just interesting findings that deserve more research. Moreover, I’m in over my head right now with my baby girl’s teething and feeding challenges. Sure, I’ll want preserve her girlhood for longer than a New York minute. But I also need to preserve my sanity

leave a comment